Previews

Historical Inspiration

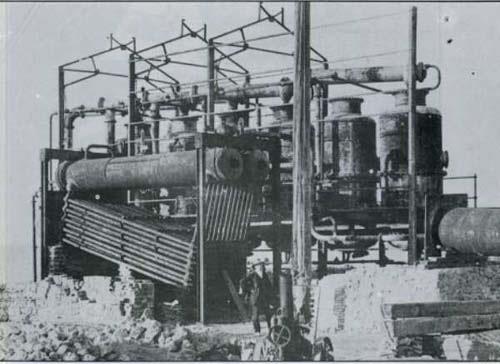

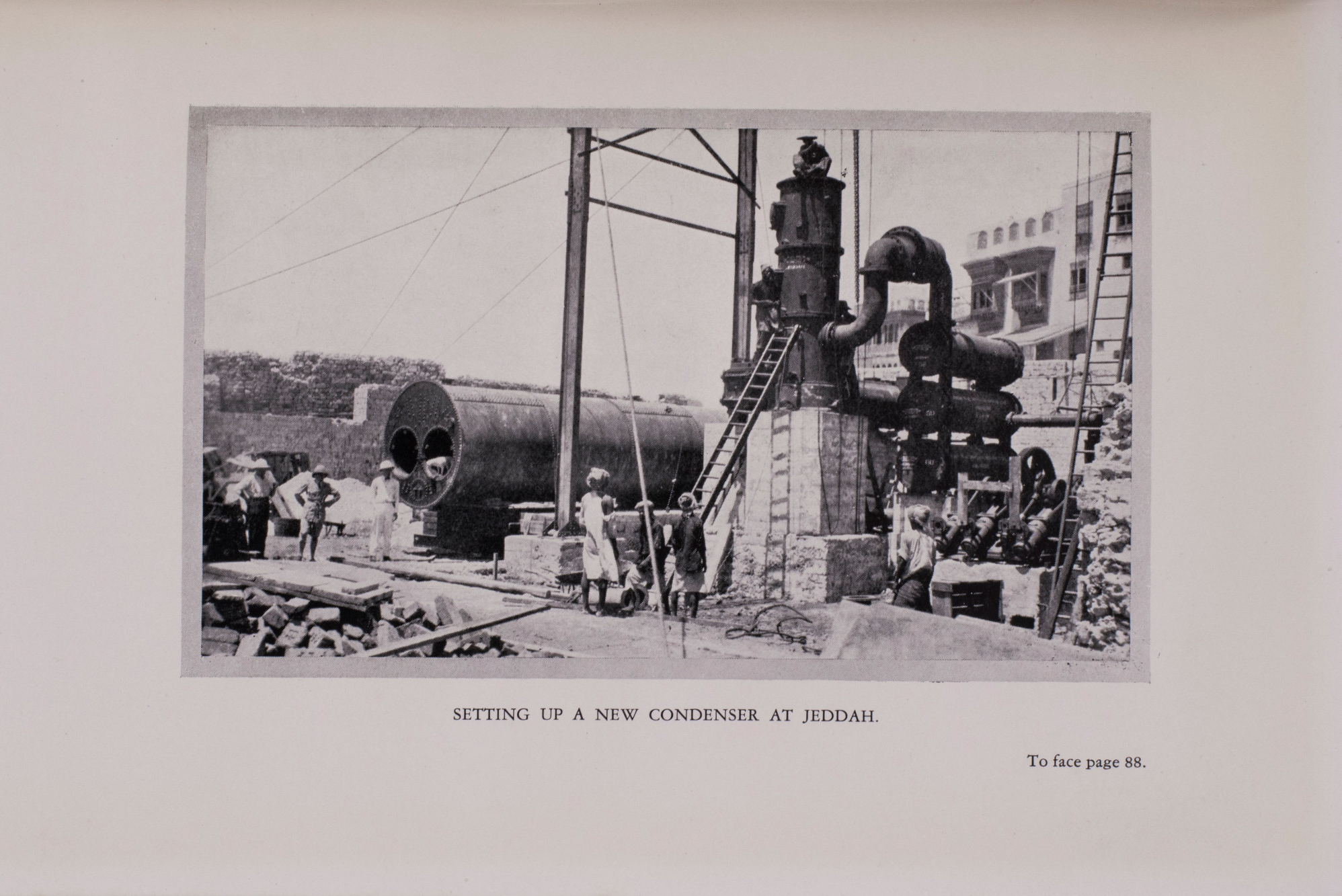

KINDASA (كنداسة – derived either from latin “condensare” or English “condenser”)

The first automated humanoid robot was a 12th-century musical band.

A water-operated programmable drum machine with wooden pegs and levers that controlled percussion. The drummers could be made to play different rhythms and patterns simply by rearranging the pegs. This ‘robot band’ could perform more than fifty facial and body actions during each musical selection.

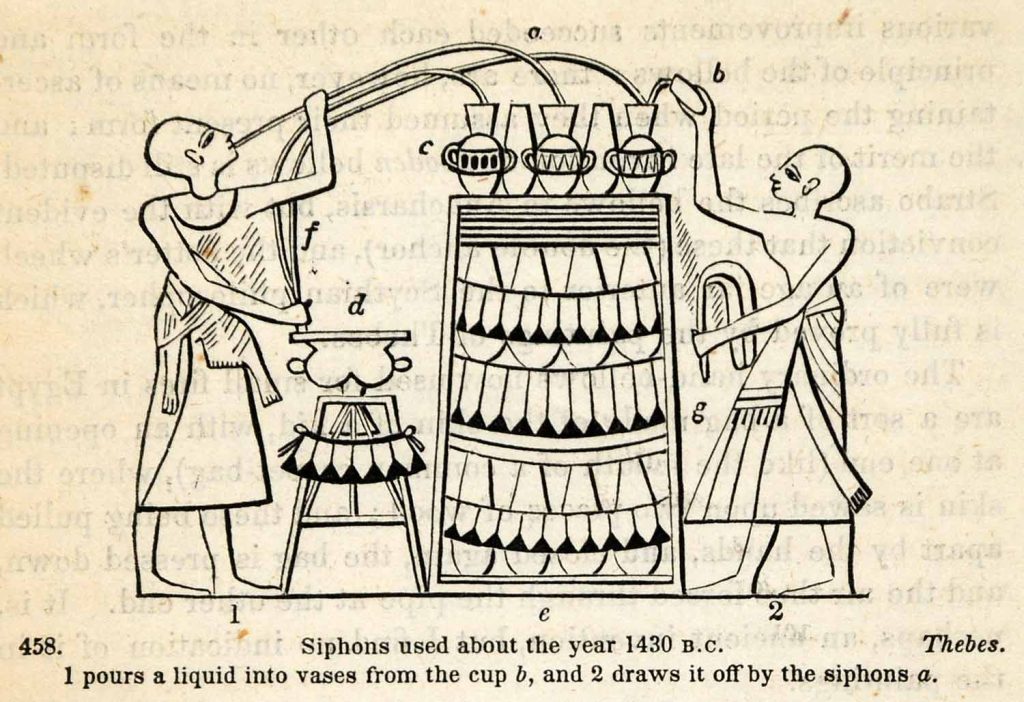

Ismail Al-Jazari invented and recorded over 100 devices, shaping the foundations of mechanical engineering. Thanks to the centuries-long Translation Movement and vibrant trade and cultural relations, he built his work upon Egyptian, Greek, Persian, Indian, and Chinese engineering.

The result was water-operated clocks (for worshippers to know the prayer times), perpetual flute machines, drum machines, fountains, hand washing devices, and machines for raising water from ponds, rivers, and flowing canals, the crankshaft (essential to all modern piston and car engines), the flushing mechanism, multi-dial combination locks and many more.

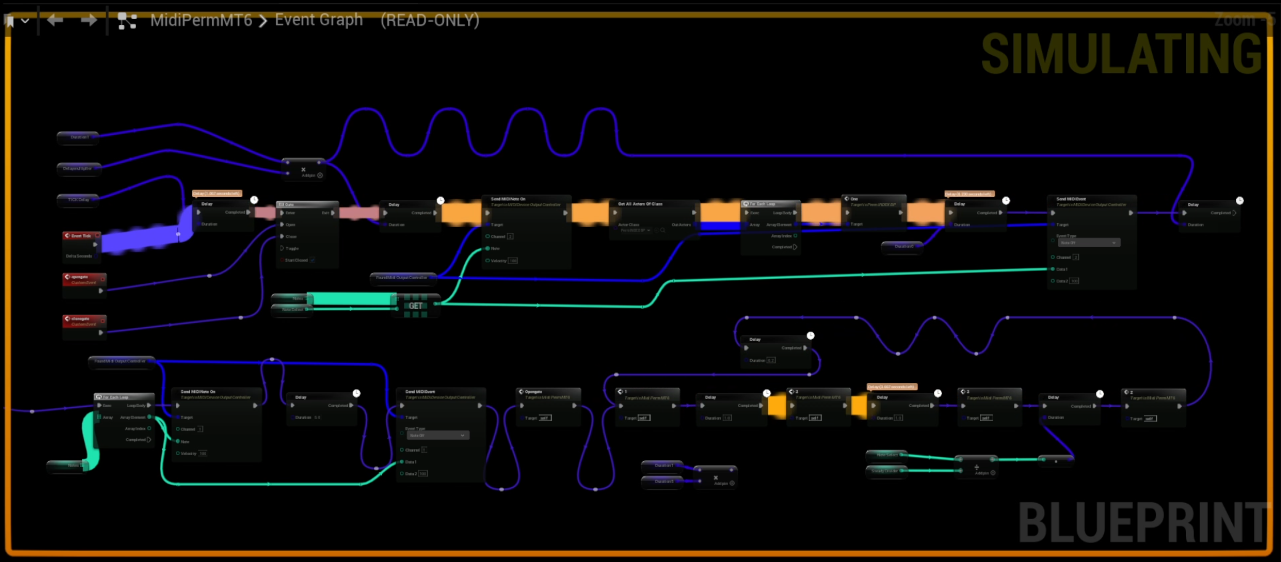

Like Al-Jazari’s clocks and musical automata, I compose using mechanical descriptions without timelines, grids, or fixed BPMs. Instead, I weave sets of rules to build a “musical-visual automaton” for each scene to unfold dynamically.

Through these rules, I simulate and regulate rhythms, visuals, movement and progression procedurally—sometimes in feedback loops. Moving arms, blinking, eye contact or avoidance, birds, sky, wind, gravity, physics, time… all carefully woven together.

The rest is intuition.

Al-Kindasa – Jeddah

++ Notes ++

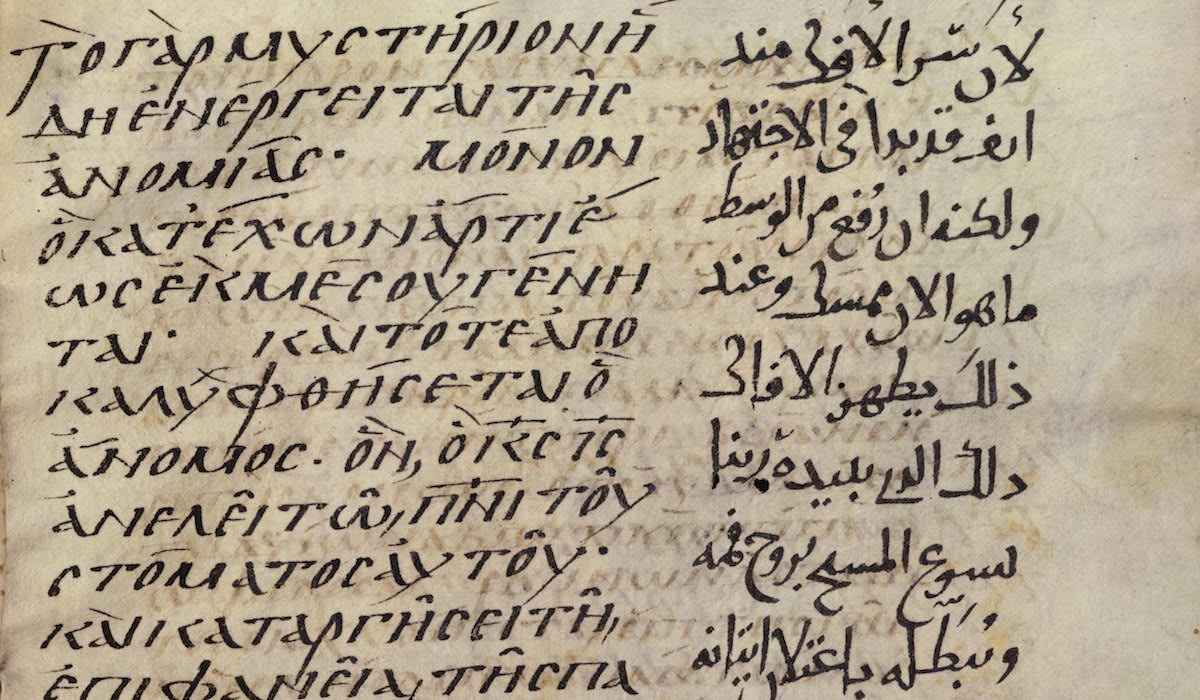

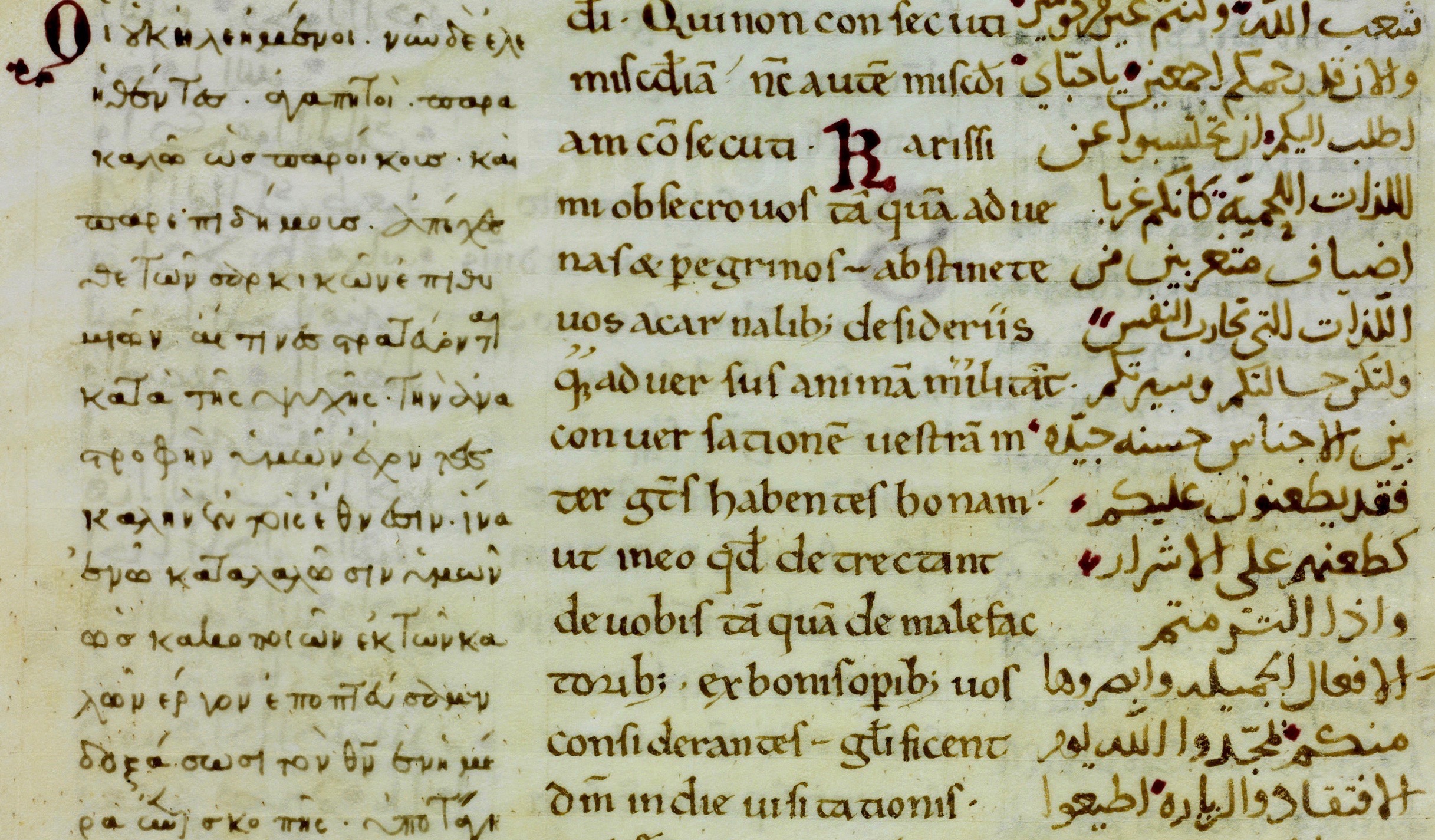

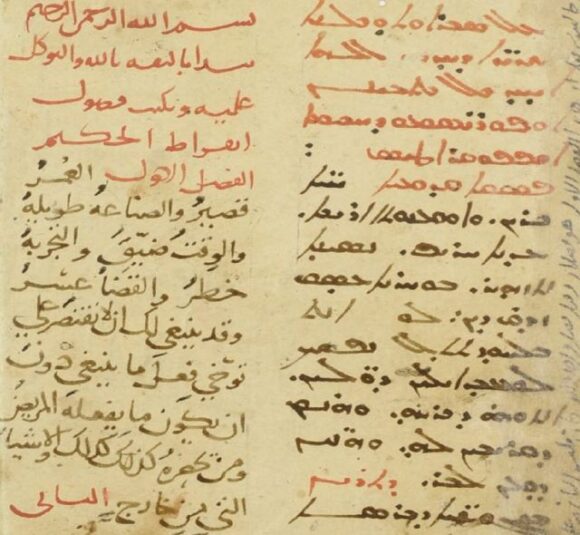

The Graeco-Arabic translation movement was a large, well-funded, and sustained effort responsible for translating a significant volume of secular Greek texts into Arabic. The translation movement took place in Baghdad from the mid-eighth century to the late tenth century.

While the movement translated from many languages into Arabic, including Pahlavi, Sanskrit, Syriac, and Greek, it is often referred to as the Graeco-Arabic translation movement because it was predominantly focused on translating the works of Hellenistic scholars and other secular Greek texts into Arabic.

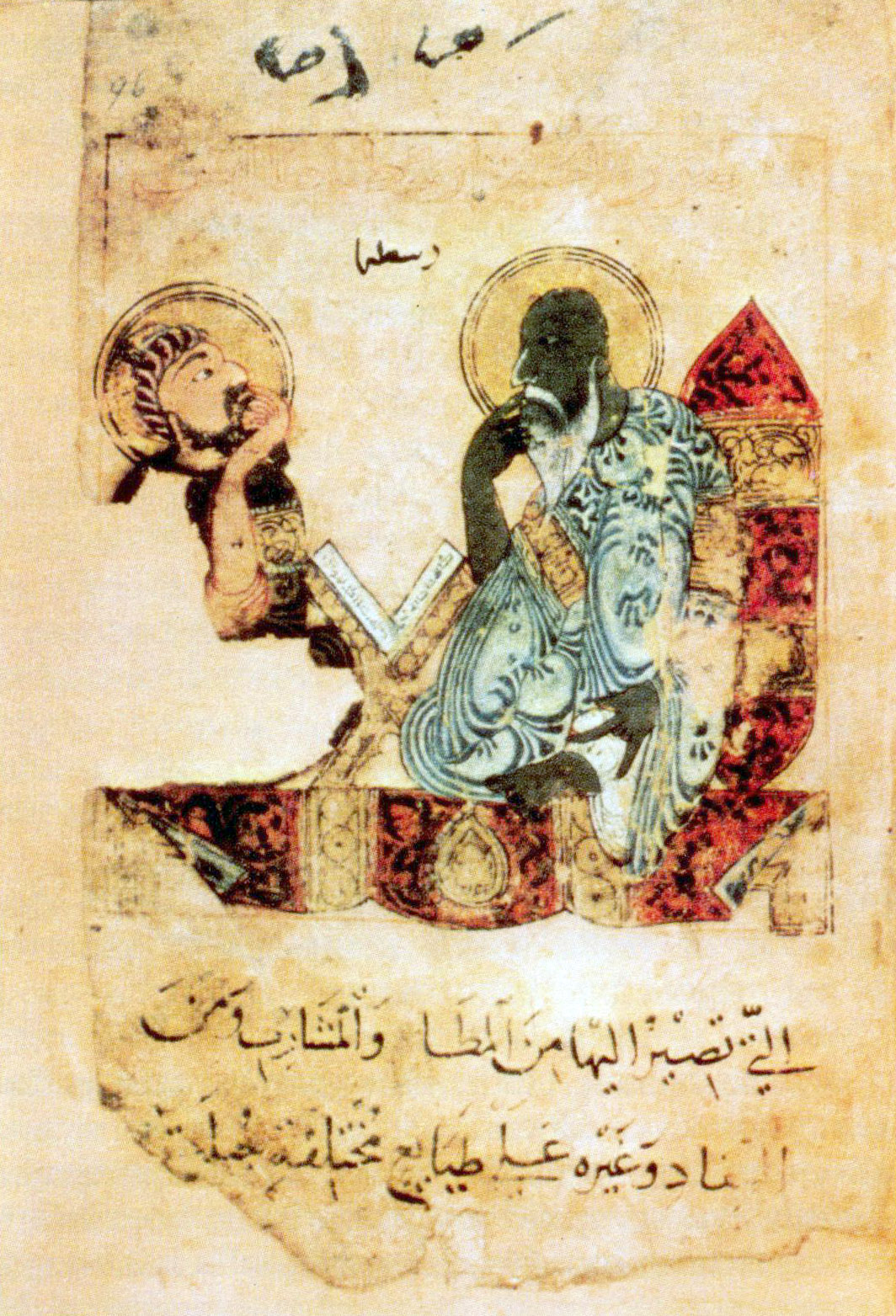

Aristotle depicted in the Kitāb naʿt al-hayawān manuscript (13th century)

Why this process?

Why this process?

While AI is becoming a bigger part of music and art, it’s not the only path forward.

I’m interested in a “handmade”, human centric kind of generative systems—one that doesn’t predict outcomes based on massive data, and unfolds in real time. While I have other wonderful uses for AI, my process in Kindasa simply isn’t about optimization and production speed, but a slower, parallel approach to technology and especially generative art; an invitation to explore deeper what is already available to us.

To create these systems, I find myself analysing real-world patterns—how people move and navigate space, how they make or avoid eye contact in public, how movement and rhythm emerge. Describing, programming, and even distorting these behaviours isn’t about perfect reconstruction or hyper-realism but about observing them in a new way.

These ideas aren’t new. They echo earlier ways of thinking about machines and generative art, from Al-Jazari’s automata to pre-digital systems of procedural composition.

Now, I’m using Unreal Engine’s Object-Oriented Programming—built to mimic real-world mechanics—which I’ve also used as a research assistant for training robots’ “common sense” at the Institute for AI in Bremen from 2018-2020.

I keep coming back to the idea that technology and art evolve together in loops rather than straight lines.

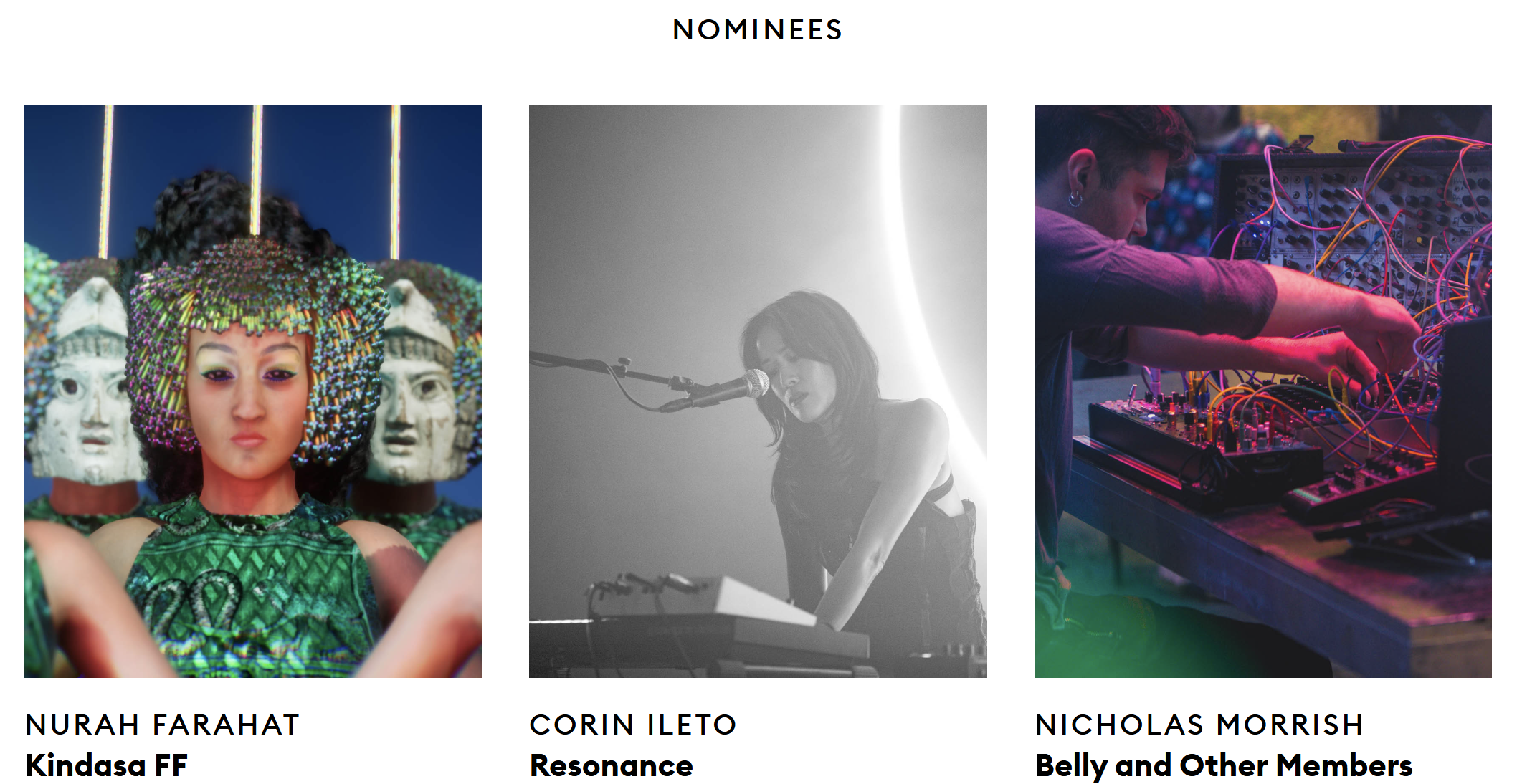

Honorary Mention - PRIX ARS ELECTRONICA 2025

FORECAST FORUM 2025

NORDMEDIA - SAMANDAR INTERNATIONAL 2024

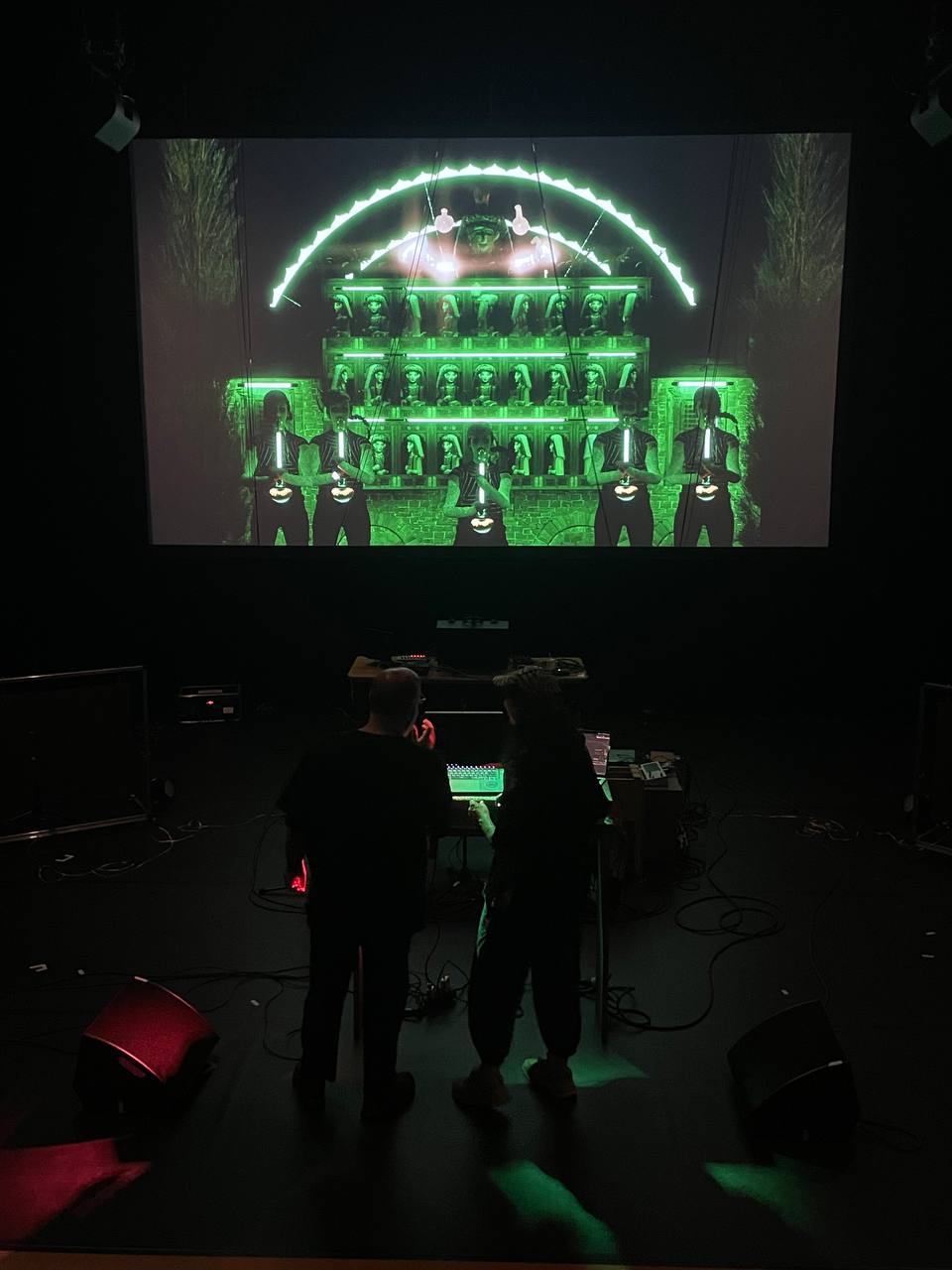

OPEN SPACE DOMSHOF 2023

OKTA COLLECTIVE - VORSPIEL BERLIN 2022

MACHINE THEATER - Senator für Kultur - Bremen 2021

CAIRO VIDEO FESTIVAL 2021

MIMIC (Lamia's Song) - Goethe Institute Digital Residency 2020

Mimic is an algorithm-mechanical family portrait. My entire algorithmic practice was influenced by an older sister who counts and repeats actions (in sets of 3’s), and by former personal superstitions about numbers. I copied her as I came into awareness of the world around me. From finding the best fit for words on my fingers to adding license plate numbers: I ended up here, programming. These number games now algorithms.

I’m portraying this relationship through this hand/number game in a style inspired by the number games we played growing up in Cairo. I dedicate this song to Lamia.

The Riddle/Numbers driving the simulation:

Nothing is random in all of the programming except for the blinking and eye movements.

I’m using a specific set I found while playing one of my number games. I found the first 11 sequences in Cairo in 2014, and found the remaining 2669 sequences in 2017 in Algorithmic Thinking class with Frieder Nake (Pioneer of Computer Art/ Computer Scientist/ Mathematician/ Professor at University of Bremen, and HfK-Bremen).

The best way I found to experience and enjoy the nature of the sequences is to solve this riddle:

Mimic, mimic

If you want

The sisters’ gimmick

Remember how it all began

From high to low,

Where did each number go?

1

5

6

7

2

3

4

9

8

(I’m also happy to provide the solution and more to whoever is genuinely interested, just drop me an e-mail on: nurah.f@gmail.com)